Il Posto (Director: Ermanno Olmi): Sadly, what makes this late gem of the Italian Neorealist movement so relevant to contemporary audiences is the fact that office work has changed so little in the 50 years since it was made. You will nod, smirk and wince in recognition at almost every step in young Domenico’s initiation into the world of work.

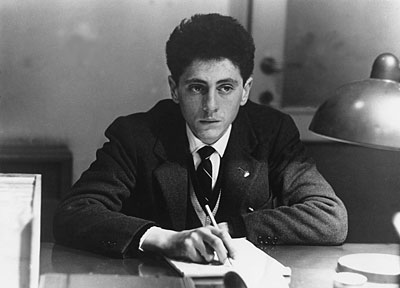

We first meet our protagonist (played with appropriately wide-eyed apprehension by nonprofessional Sandro Panseri) trying to squeeze in just a few more minutes of sleep before he has to ride the train from his outlying suburb into Milan to take a series of tests for an entry-level clerk’s job at a big company. Money is tight, as evidenced by the presence of his bed in the kitchen of the family’s crowded apartment. We learn that due to financial pressures, he’s had to abandon his studies early and his parents are eager for him to land a “secure job for life” with this unnamed firm. Although he seems like a bit of a dreamer, he’s an obedient son who doesn’t question this unwanted detour in his life. If anything, he seems happy to be able to escape the crushing boredom of home life, and the oppressive influence of his parents.

During the day of tests, he strikes up a friendship with the prospect of romance with the cherubic Antonietta (played by 15-year-old Loradana Detto, who went on to become the director’s wife), who’s applying for a typist’s job. During their lunch break, they window shop and enjoy the small luxury of a cup of coffee, discussing what they’ll be able to do with their paychecks should they be hired.

When he gets the job, Domenico is thrilled at the prospect of seeing the lovely Antonietta every day and continuing the courtship, but as fate would have it, he’s assigned to another building and another lunch shift, and their paths rarely seem to cross. Instead of the clerical job he was expecting, he’s assigned to a position as a messenger, with the promise that he’ll be reassigned as soon as a clerk’s job becomes available. As he gets to know the routines of the office and the rituals of working life, the film pulls back to show us brief glimpses into the lives of some of the other employees, including the clerks Domenico is destined to work alongside for the rest of his career. Humane and heartbreaking, these side narratives add weight to the story, driving home the point that life for these office drones is elsewhere. One man, mocked as “Sleepyhead” by the other clerks, is a struggling writer, endangering his eyesight by writing deep into the night. Another is a talented tenor who insists on singing arias whenever he’s with friends. We see the financial struggles of another clerk, and her problems with her children.

A central scene takes place at a New Year’s party at the employee social club. Domenico has shown up hoping to see Antonietta but finds himself sitting alone. After an older couple invite him to sit with them, he’s gradually caught up into the forced merriment whipped up by the hired band, and the impression is of people thrown together, with nothing in common except their place of employment, but trying desperately to make the best of it. If you’ve ever been to a company party, you’ll ache with recognition and sympathy.

When a vacancy finally allows Domenico to assume the clerk’s position he thinks he wants, it’s actually a moment of terrible sadness and resignation, and it doesn’t take him long to recognize the atmosphere of despair that he’ll be living in for the rest of his working life. It’s a terrifying moment and the film leaves it hanging in the air like an acrid smell.

Olmi’s film is deeply humane and there are no real villains. At worst, the bosses are indifferent. But it’s clear that the workplace crushes the humanity out of its victims. The gleaming modern offices of the 1960s (or the 2010s) are really no different than the factories of the previous century, reducing their human workers to functionaries who will struggle to retain their humanity outside of office hours. This Kafkaesque world of rules and hierarchies has been mined for laughs recently by films like Mike Judge’s Office Space, but Olmi’s depiction of a young man being led like a lamb to the slaughter will simply break your heart, even if you might be weeping as much for yourself as for the young innocent on the screen.